Join Us Monday, December 9th, at 6 PM: Our Last Chance to Be Heard

This is the final school board meeting before they vote on the fate of our small schools. Your presence, whether you speak or not, will send a powerful message: our small schools matter. Together, we can hold decision-makers accountable and demand solutions that prioritize students over developers.

A System Designed to Keep the Money Flowing

What if I told you that the long-range plans shaping the West Linn-Wilsonville School District aren’t created by educators or the Long Range Planning Committee (LRPC) as you might assume, but by developers, architects, and land-use planners? Since 2012, a systematic process—what I call “The Machine”—has taken root, designed for one purpose: to pass the next bond.

It began in January 2011, when David Lake, a longtime LRPC member, proposed documenting a step-by-step process for passing bonds [1]. On paper, this might seem like a pragmatic idea. In practice, it transformed the planning process into a rubber stamp for preordained outcomes. Community involvement? Reduced to a formality. Decisions? Made behind the scenes by a closed circle of architects, consultants, and planners with vested interests.

The Reimbursement Districts: A Developer’s Dream

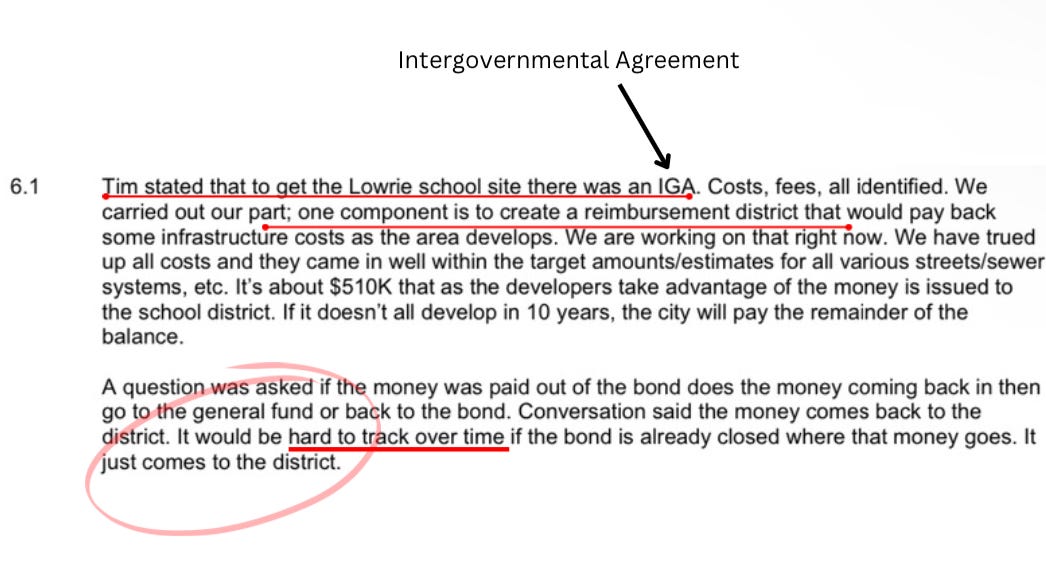

Intergovernmental agreements (IGAs) have enabled the district to create reimbursement districts, which allow the district to recover infrastructure costs (roads, sewers, etc.) from developers and new homeowners over time. This sounds logical—until you consider the implications:

• New Schools vs. Old Schools: Reimbursement districts incentivize building new schools at the urban growth boundary (UGB), where development fees can be collected, rather than maintaining existing neighborhood schools like Bolton [2].

• Untraceable Funds: Once the district receives these payments, they are no longer tied to the original bond. As noted in meeting minutes, “It would be hard to track over time… It just comes back to the district” [2].

In essence, taxpayer-funded bond dollars are transformed into untraceable revenue streams. Who is ensuring accountability?

Excise Taxes: Greenlighting Construction, Not Education

Construction excise taxes—fees paid by developers on new builds—provide another steady revenue stream for the district. But these funds are only accessible if the district supports urban expansion [3]. This creates a troubling incentive to prioritize construction over community needs, even if it means paving over green spaces or building schools in areas no one asked for, like Athey Creek.

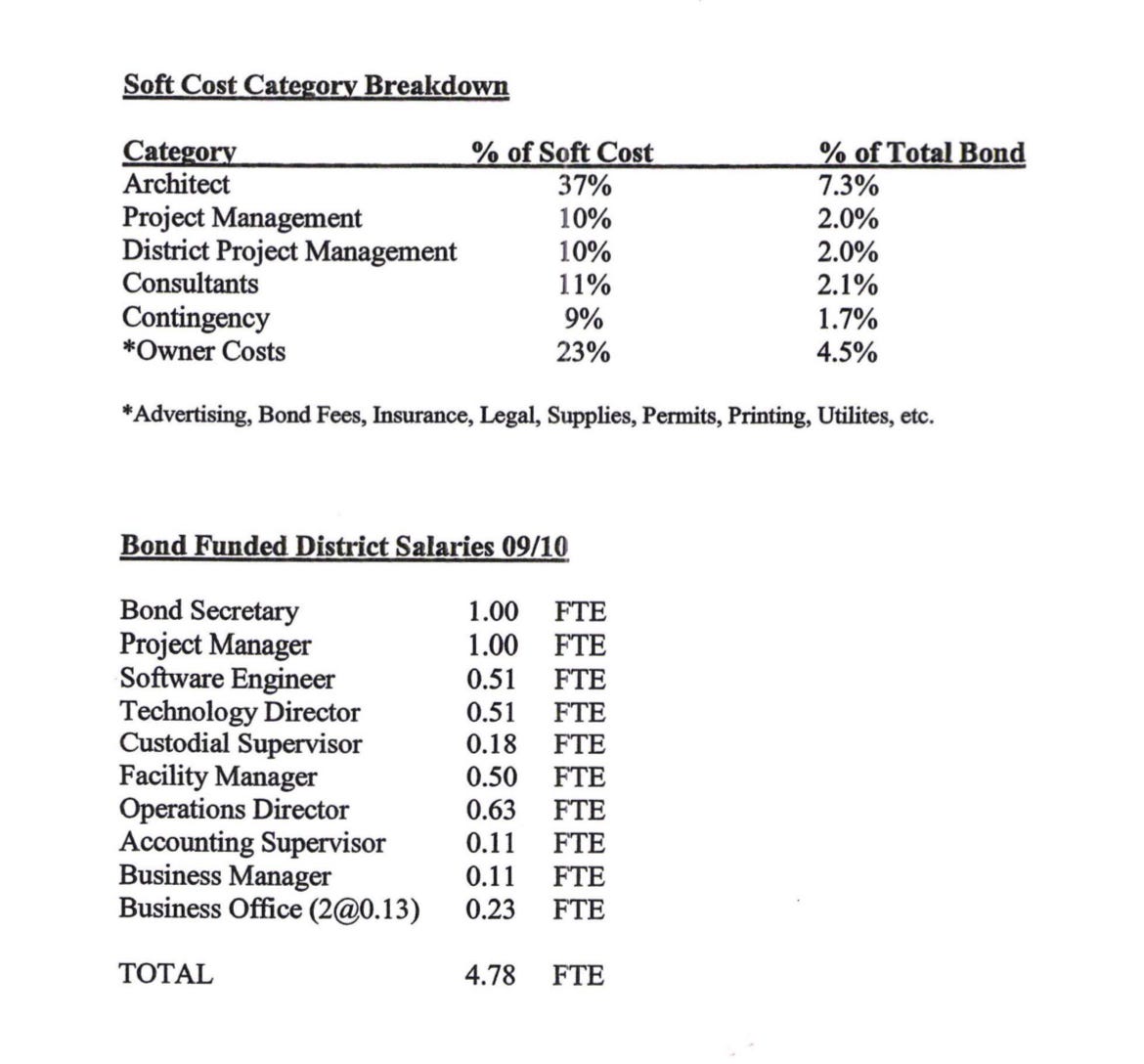

Soft Costs: Who Really Benefits?

A breakdown of the district’s “soft costs” reveals significant expenditures on architects, consultants, and project managers—all of whom have a vested interest in keeping “The Machine” running [4]. These roles are listed as essential to bond planning, yet they siphon funds away from classrooms and student programs.

Enrollment Projections: The Manufactured Crisis

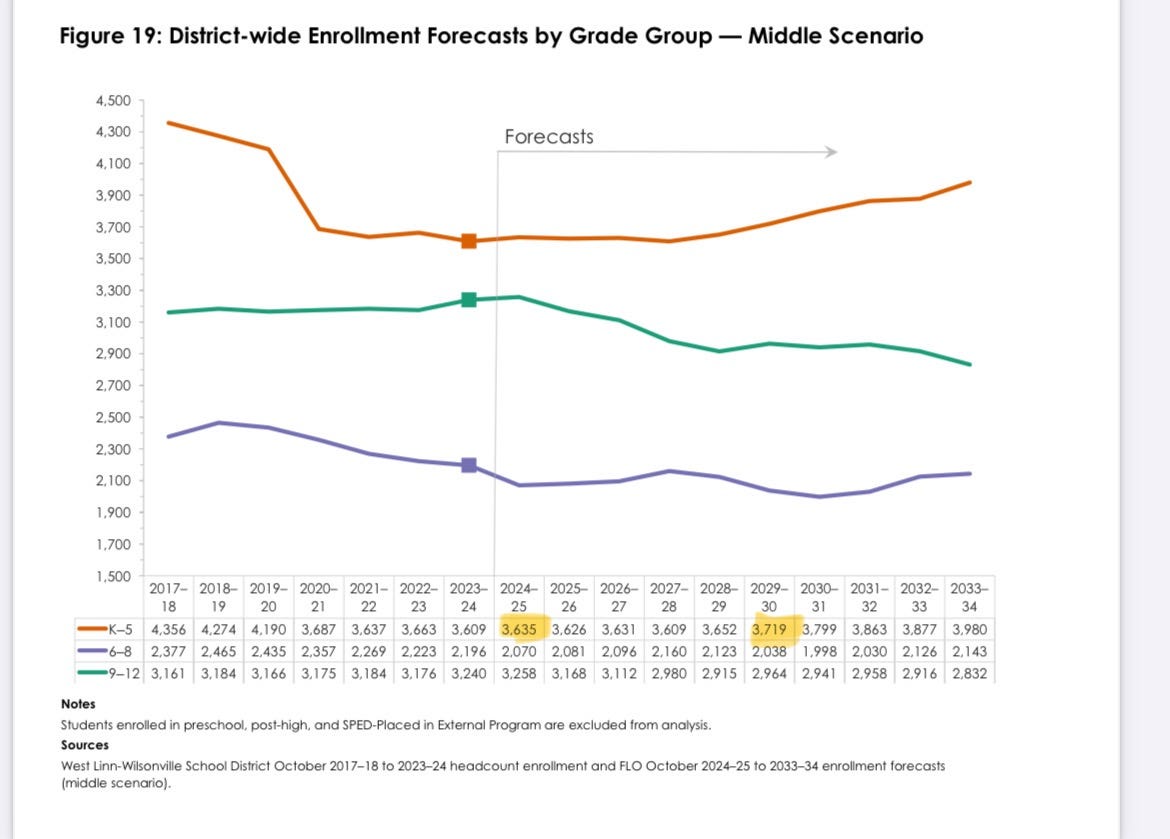

We are told enrollment is declining and that schools must close to avoid larger class sizes and program cuts. But the data tells a different story:

• K-5 Enrollment Growth: In all three scenarios (high, medium, low growth), primary enrollment is projected to increase by the end of this bond cycle [5].

• Capacity Redefined: Over the past two bond cycles, the district has shifted how it defines school capacity, conveniently altering the narrative to fit its goals [6].

If schools close now, what happens in five years when enrollment rebounds? The solution will likely be to build another school—on another bond.

The LRPC: Dedicated Volunteers in a Flawed System

The Long Range Planning Committee, once a cornerstone of community input, has become little more than a rubber stamp in recent years. However, it’s important to acknowledge that the LRPC is made up of dedicated volunteers who genuinely want to serve their community and improve schools for all students. Many of them bring valuable perspectives and expertise to the table.

Unfortunately, the system they inherit sets them up for limited influence. Current members, many of whom joined within the last two years, are handed “The Process” and guided through data provided by longtime consultants like Flo Analytics and Arcadis Architects [6]. These firms, with decades of ties to the district, are exempt from competitive bidding—a loophole that cements their influence over every new project.

Despite this, the LRPC members continue to ask thoughtful questions and offer feedback where they can, even when faced with rigid frameworks and preordained outcomes. They deserve better—more transparency, more autonomy, and a genuine opportunity to shape the future of our schools.

What About the Students?

While “The Machine” churns on, our students are the ones left behind:

• Wilsonville’s New Schools: Despite state-of-the-art facilities, students in Wilsonville are failing to meet academic standards.

• West Linn’s Small Schools: Beloved neighborhood schools are under threat, despite strong academic performance and high scores on satisfaction and belonging surveys.

The district’s priorities are clear: protect its own interests while cutting programs, increasing class sizes, and closing schools.

There Are Better Solutions

Closing schools is not the answer. Here’s what we could do instead:

• Cut Three School Days: A minor adjustment to the calendar could solve the budget shortfall without sacrificing neighborhood schools [7].

• Apply for Grants: Federal and state grants could fund innovative programs, such as creating Full Service Community Schools that provide wraparound services for families.

• Focus on Academic Excellence: Small schools consistently outperform larger ones in both academics and student happiness. Keeping schools small is an investment in our children’s future.

Join the Fight to Save Our Schools

It’s time to stop prioritizing developers and start putting our students first. Join us on Monday, December 9th, at 6 PM for the school board meeting. Together, we can demand transparency, accountability, and a commitment to keeping our neighborhood schools open.

Let’s remind the district that the purpose of long-range planning isn’t to benefit architects, consultants, or developers—it’s to ensure the success and well-being of our children.

Where is the meeting? I can’t find the meeting location on the district website.

Were you successful? I am in a different state but similar challenge.